With this review I finish writing about the stack of photobooks I bought in January (and with this post I'll start keying "photobook" as one word, a usage which seems to have legs. Although the results of a "photo book" google search are nearly five times greater than that of the one-word search, the

cool kids

are going for the the latter. Anyway, I've stopped buying books for a while but before my sabbatical from hoarding began I binged on another stack of photobooks. A stack that, um, may be even bigger than the stack that inspired this project I started for myself. ( The Japanese photobook

Domestic Scandals, which I wrote about a few weeks ago, is from this new pile.) Blame it, if blame you must on what might be called Retail Therapy but, after professional consultation, may more accurately be termed Retail Treating Surface Symptoms By Covering Them Up Superficially And Not Really Filling The Void At All Not Even A Liddles. At any rate (really, at the rate of once a week, which I've barely missed the last few weeks but chalk it up to getting home late from Saturday family visits), I'll continue writing about photobooks singularly or plurally. I'm a little intimidated that Walker Evans's classic monograph

American Photographs

is in this queue, because I find it easier to write about the lesser known and the previously unfamiliar (to me or to you) than about one of the undisputed classics of the form.

Anyway, the following article was first published as

Book Review: Foto en Copyright Vol. 2 by G.P. Fieret on Blogcritics.

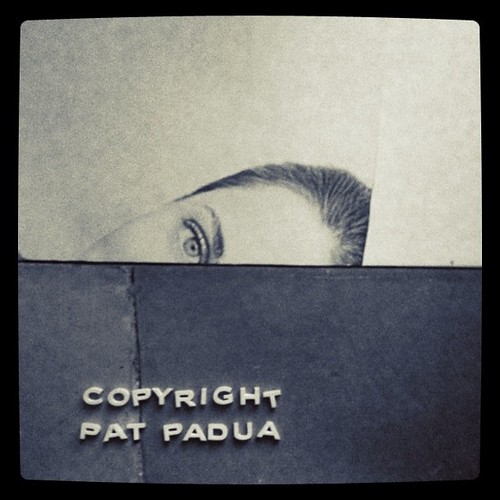

A G. P. Fieret iPhone app would be easy to design. It would be something like DoodleBuddy: you can choose where to place circular copyright stamps, and how many; select and address stamp with the artist’s full name; select and size the artist’s signature. Desaturate, add contrast and grain and there you go: a basic template for the photographer’s signature look. But as with life, art is not as easy as it looks. Behind the over-protective copyright marks, which may seem like a gimmick but was born of paranoia, the vision behind the late photographer’s unadorned images is genuine. And if particulars can be imitated, the essence is unique.

The

Fotomuseum den Haag released its

first collection of G. P. Fieret’s striking nudes and street photography in 2004, in an out of print edition now prized by collectors. So by popular demand, the museum has issued

Foto en Copyright by G. P. Fieret Vol. 2

, a selection of another 160 photographs from their archive of 2500 prints from Fieret’s studio. Sadly, the artist died in early 2009, but he left behidn a vibrant and original body of work. This volume scales back a little on his trademark copyright stamp and John Hancock, though these are still well represented. But after that aesthetic jolt, the chance to some of his prints without the distractions give you a view straight from Fieret’s remarkable eye.

In a world full of street photographers it can be hard to stand out, and while nostalgia and unfamiliarity helps make these images from Hague streets in the 60’s strange and new to American audiences, the grainy vision, stark but also human, is always evident: in the party-hatted elderly attendees at a museum opening; in an intimate portrait of Japanese artist

Yayoi Kusama; in masked biddies on a parade route ; in a child taking her baby doll for a stroll. And throughout, there are Fieret’s women, fully engaged with the artist, and clothed or disrobed they really do make love with their eyes to the man behind the lens. Cats provide the occasional accent to his human landscapes: one white feline regally stands guard as a near abstract counterpoint to the daisies gracing the black maw of an underexposed garden background. G. P. Fieret will not remain underexposed. Get this while you can.